Lost In Translation

Words and the "Bhagavad Gita"

Once again, I bring this to you on a Monday! Darn, I gotta write these a little earlier… Anyways, enjoy. :)

Do words mean what we think they mean? This is the question I’ve been returning to more and more these days. It’s certainly not a new question, to be sure. Rhetorical analysis has been around for thousands of years, and I’m not nearly as well read as most of the scholars who tackle the paradoxes of language. Still, I find myself routinely amazed by the different ways people interpret and experience words.

“Get a vaccine.” Simple enough. Yet, people find all kinds of meaning in these three words. For some, “get a vaccine” means:

“Stay healthy and safe, take care of my friends and family, believe in the science, move towards a more ‘normal’ world.”

For others:

“Blindly trust the crooked medical establishment, bow down to the Democrats and the left-wing media, get injected with a drug that isn’t tested enough, give up my freedom.”

Now, one might say, “Those other words you described are just different opinions that people have. The words ‘get a vaccine’ still mean something objective and simple.” I used to agree with that sentiment, but I’m finding the evidence for the objective meaning of words less and less persuasive1. It seems to me that words — whether read or heard — bring about images, feelings, and relationships into the consciousness of my mind and that this process happens completely out of my control. That is, I simply happen upon the meaning of words with little understanding as to how that meaning is precisely constructed. How can I be sure that the objective meaning of words truly exists if, from my own perspective, I can’t even tell someone how I came to understand those words?

I can think of no better example demonstrating this conundrum than when I attempt to explain the meaning of the “Bhagavad Gita,” a seminal Hindu text, to friends.

*****

What’s the story?

Many scriptures/texts codify the Hindu religion as it is practiced today. They include the Veda, the Upanishads, the Ramayana, and the Mahabharata. Some of these texts are instructional (telling worshipers how to follow certain rituals, how to pray to God, etc.), and others are mythological (epic poems that tell stories of God). The Bhagavad Gita is a little bit of both. It is a piece of the larger Mahabharata — an epic poem about the god Krishna that is ten times the length of the Illiad and the Odyssey combined — but acts as a kind of “self-help” text for spirituality. Here’s the gist2.

There is a great war between the cousins of the Bharata family. The five Pandavas, the brothers of goodness and virtue in the family, are fighting against one hundred Kavuravas, the brothers of evil. One of the Pandavas, Arjuna, asks his chariot driver to take him to the center of the battlefield so that he can survey the current state of affairs. The charioteer is Krishna, an incarnation of God as a human.

I have to take a momentary detour here to note that my family name is intrinsically connected to the Gita. My full last name is Parthasarathy (a Sanskrit or Hindi name), which literally translates to:

Partha = another name for Arjuna

sarathy = charioteer

Parthasarathy = Arjuna’s charioteer = Krishna

As Arjuna looks at the battlefield, family fighting against family, he lays down his arms and tells the Lord that he won’t fight. He is broken mentally, physically, and spiritually. He doesn’t see how the war between good and evil can be morally justified if he must kill his brethren in the process. Speaking his next eighteen discourses in verse, Krishna admonishes Arjuna for his lack of courage and implores him to continue the fight. Krishna tells him that it is his duty (dharma) as a warrior to fight and that so long as he acts with conscience and no worldly desire for fame and fortune, he is doing the right thing.

For me, what animates the Gita is the seemly intractable paradox between the non-violence typically espoused by Hinduism — and in the Gita itself — and the central thrust of Krishna’s message to Arjuna which is to fight a bloody war. Many have commented on the Gita’s apparent self-contradiction, from Gandhi to Paramahamsa Yogananda to Aldous Huxley. What I can say, from having read the text many times, without appropriate context and definitions of words, it is difficult to understand the subtleties of the Bhagavad Gita’s message.

Unfortunately for people in the West, you will encounter many problems with the Gita’s text because words like yoga, karma, and even God can mean VERY different things that you think they mean.

*****

A Stickler for Words

Yoga has been appropriated and commodified by an American fitness industry that often distorts the meaning and purpose of yoga to an absurd degree. As a result of this, you might be surprised to hear that the yoga one does at a typical yoga studio in LA is just one branch/aspect of yoga: hatha yoga. To be clear, I’m not suggesting that people who are non-Indian shouldn’t do yoga; so long as you do some basic work to understand the intent and origins of hatha yoga, I think you should be free to practice yoga for the sake of your physical and mental betterment. However, this distortion in the meaning of yoga makes it difficult (even for me) to understand how the Gita uses it.

Yoga in Hinduism refers to a broad range of exercises and disciplines to develop and maintain a spiritual practice. It includes physical and mental exercises, meditation, service to the community, and intellectual inquiry. Krishna describes these various yogas in the Gita, and different facets of yoga make up the various chapter headings — chapter 3 is called “The Yoga of Action,” and chapter 4 is called “The Yoga of Wisdom.”3

When I read through the Gita, I had to consciously scrub the Westernized interpretation of the word yoga from my mind and attempt to discern the meaning of the word in context. I can only imagine that others, who have not had an upbringing in Eastern philosophy, might read yoga and simply envision someone in a “downward dog” pose and assume that that is all there is to glean from the sentence. A Western reader attempting to open their mind might need to spend years until they can read those passages and feel the author’s intent in their mind and body.

The same goes for karma, which most people in the West translate to: “what goes around comes around.” Not a terrible summary. But it leaves out concepts like reincarnation, fate and its role in our lives, the soul’s permanence regardless of the death of the body, etc. If you read karma and assume that it’s simply referring to people's actions against one another, you will miss important insights.

Perhaps the word God is actually the trickiest word in the Gita. Most people exposed to this word will imagine that it is some form of the Abrahamic God — that Krisha is the God featured in his particular myth and that he is giving a discourse to humans. You might then be confused by passages like:

How can God be both the offered and the offering? How can he be both the doer of worship as well as the receiver of it? God is both human and also a god?

Well, the Hindu conception of God is rather different from the one in Christianity or Judaism (though I’m no expert). In many ways, God (bhagavan) is better translated into English as “oneness” or “the spirit of all things” or “the Self.” It is the soul of every being, animate or inanimate. It pervades everything around us. It represents both good and evil. It is that which humans aspire to, but also the light that is in all of us. Hard to tackle the full meaning, but it’s much closer to a kind of yin and yang, or the Tao (a Chinese word), which is generally translated as “the way.”4

And here’s the rub. There isn’t a good translation from Sanskrit to English for God. I could spend hours attempting to talk to non-Indian friends of mine about the Hindu conception of God. Even if they are open-minded and attempt to process all of my speech, it is unlikely they will fully absorb my understanding of God in the Hindu context. Because they simply haven’t lived my life or come from my background. That’s not to say that what they take from the Gita is useless. Quite the opposite. I simply mean that the word God has very little intrinsic meaning. It only has the meaning that each person takes from it when they hear/see the word and feel it in their consciousness.

*****

What does it all mean?

Here’s a passage from the Bhagavad Gita that almost summarizes the whole work:

I talked about this passage and its contents to friends before. After reading this passage, some people think this passage means “don’t have regard for the consequences of your actions, because none of it matters anyway.” Which sounds mildly existentialist and pretty awful. In fact, this passage means the opposite to me. It means, “act with conscience and morals but be unattached to the results that are out of your control.” Of course, people are entitled to their own opinion. As I said earlier, there isn’t any intrinsic meaning to these words, per se. Hindus argue about the meaning of these passages all the time. However, I would provide additional textual evidence to support my meaning, as well as experience studying other Hindu mythology.

These two verses are the basis for Gandhi’s message and legacy. He once articulated, “As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. This is the divine mystery supreme. A wonderful thing it is and the source of our happiness. We need not wait to see what others do.”

If we change ourselves, we inspire change in others. One does not need to cling to the results of actions to make a change. Just because I didn’t win an award, or hear praise from a crowd, or make a profit, doesn’t mean I shouldn’t act for the well-being of others. In fact, I am obligated to help others. That, I would argue, is the essence of the Bhagavad Gita.

One of my favorite passages from this text is:

“Cheap, sentimental words.” That’s a powerful statement coming from scripture. The text undermines itself! It says, “These words are pointing towards a truth. Don’t regard these words as the truth in and of itself.” In other words, the words don’t really matter.

Okay, they do matter. We know that. But, the idea here is, even the text tells us that the words have little intrinsic meaning. They only attempt to help us realize some meaning that we search for with our hearts and minds.

*****

A Note of Apprehension

Since this is basically a blog, I’ll be informal and share a misgiving I have with this whole essay. The last thing I want is for people to look at this essay as a sermon on religion. People who know me well know that I’m not particularly religious, even as I have great respect for the culture and traditions of my ancestors. I feel like my beliefs fall somewhere in between Buddhism and Hinduism. And, I’m agnostic as to the existence of God or a higher power, at least as it’s generally conceived of in the West.

I do, however, feel that the Bhagavad Gita is an impressive philosophical text. It is also some of the most beautiful poetry I have read in my life. It can be read as a guide to living a good life or as a historical text. It can be read like Greek mythology, as the thinking of a civilization thousands of years ago. It has passages that I’m not fully comfortable with and chapters that seem less relevant to the modern world. It’s certainly not perfect, in my view. Yet, it is full of wisdom. I would recommend it to everyone! I hope you find its message useful in one way or another.

*****

“I owed a magnificent day to the Bhagavad-gita. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.”

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Rundown

The Student Symphony Orchestra at USC put on a Spring Concert recently. I used to be a part of this orchestra when I was a student. But I have to say, they are at a whole new level now. This is UNBELIEVABLE work. Special shout-out to their music director, Adam Karelin, who was one of my first guests on the podcast. Check this out:

The Economist recently did a “Briefing” on the creator economy. It is extremely comprehensive and highly quantitative in its analysis (as The Economist generally is). I definitely recommend it.

In honor of trombonist Curtis Fuller, who passed away last week, here he is on the legendary record “Blue Train”:

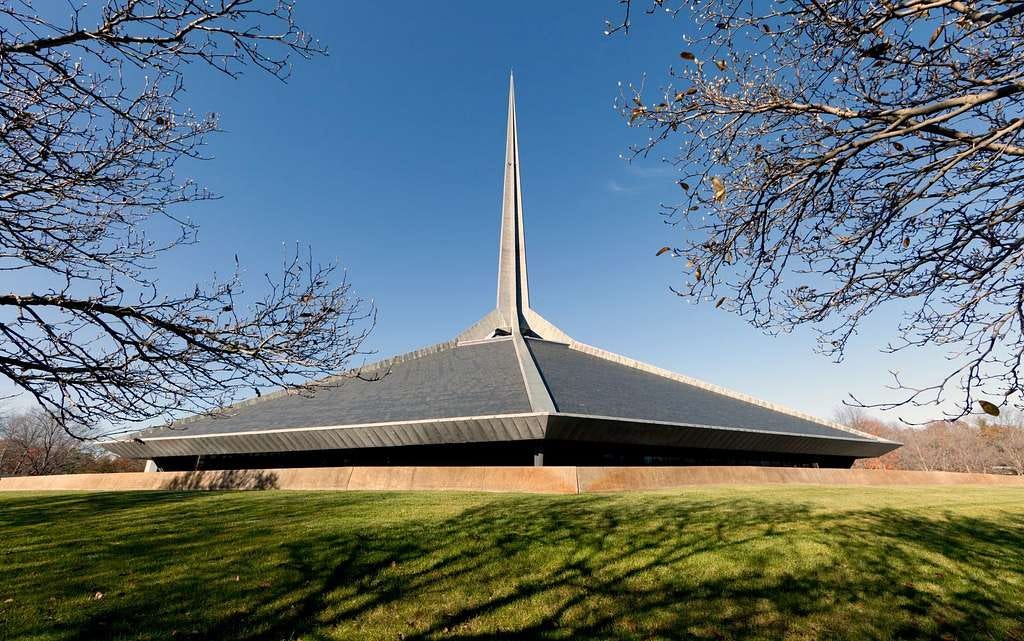

I was recently reminded of the film Columbus (2017), which starred John Cho and Haley Lu Richardson. Directed and written by Kogonada, it is both a beautiful ode to architecture — the modernist architecture of Columbus, Indiana — and an intriguing relationship drama. It defies expectations and it is deeply moving to watch, even if I can’t explain exactly why.

I don’t know how, but I recently became obsessed with these Harvard “Ames Moot Court Competition” videos! I don’t understand all of the legal jargon, but I find the interaction between the “lawyers” and the “court” really interesting. With Biden’s recent infrastructure proposal, this particular hypothetical court case — Go Glow, Inc., v. Sheila Simpson — becomes remarkably relevant. The case tackles the legality of state and local statutes/ordinances forcing government buildings to only use infrastructure manufactured in America. It may not be your cup of tea, but surely you can appreciate how knowledgeable the advocates, as well as the presiding judges, are.

Shoutout to Brooke Schneider, a friend of mine from USC, who is doing really cool work with ceramics. I know very little about how making these things actually works (I’m gonna try to get her on the podcast to explain it to me!), but the form and function of these bowls and mugs are remarkable. Here’s the link to her Instagram.

If you are interested in a comprehensive summary of the philosophy of word meaning, this is a good place to start. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is always an interesting read if somewhat hard to follow, given that I never formally studied philosophy.

This story is actually quite hard to explain succinctly, so forgive me! I hope I did it justice.

My preferred translation for the Gita is the one by Stephen Mitchell, and it is this version that I quote throughout the piece. I have perused through a few different translations with my mother — who has a working knowledge of Sanskrit — and she and I both felt that Mitchell’s version gets closest to the spirit of Gita’s meaning. A few other translations use antiquated English, full of thee and thou, making it sound like a Biblical or Shakespearean text. It sounds ridiculous and completely misrepresents the soul of the Gita, in my humble opinion.

Mitchell also has a translation of the Tao Te Ching, which I recommend.